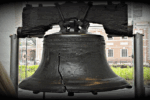

After American independence was secured, the bell fell into relative obscurity for some years. In the 1830s, the bell was adopted as a symbol by abolitionist societies, who dubbed it the “Liberty Bell”.

After American independence was secured, the bell fell into relative obscurity for some years. In the 1830s, the bell was adopted as a symbol by abolitionist societies, who dubbed it the “Liberty Bell”.

Two founding dates—1619 and 1776—and two corresponding projects—The 1619 Project and The 1776 Commission—offer sharply contrasting visions of America’s beginnings and its democratic character. The debate is not simply about when the nation was founded but about what kind of nation it has been and aspires to be.

The year 1619 marks the arrival of the first enslaved Africans in Virginia, inaugurating a system of forced labor and racial hierarchy that would define the colonies for generations. From that moment, the economic promise of the New World became inseparable from the subjugation of Black bodies. Slavery was not a marginal institution but the foundation upon which wealth, property, and power were built.

In moral terms, 1619 represents the origin of America’s contradiction—a society that prized liberty for some while denying humanity to others. The racial order established then did not simply precede democracy; it shaped the very boundaries of who was deemed worthy of freedom. The legacy of 1619 thus reveals that inequality was not an accident of history but an organizing principle of the early American experience.

The year 1776, by contrast, marks the Declaration of Independence—the formal articulation of America’s democratic ideals. “All men are created equal,” Jefferson wrote, invoking a universal language that would inspire liberation movements across the globe. Yet those same words coexisted with slavery, dispossession, and exclusion. The revolution that claimed liberty as its cause left millions unfree.

Here lies the enduring paradox: the freedom articulated in 1776 emerged from a social order established in 1619. The ideals of equality and self-rule were conceived within a world that depended on inequality and bondage. The two dates are not opposites but reflections of a single American dilemma—how to reconcile high principle with historical practice.

The 1619 Project, led by journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones, reinterprets American history by centering the role of slavery and Black struggle in defining the nation’s democracy. It argues that the ideals of 1776 only became real through the resistance of those whom the nation excluded. The 1776 Commission, created by President Donald Trump, counters that view by celebrating the Founders’ vision as essentially pure. It presents America as a nation whose course has been one of steady moral progress, not foundational hypocrisy. These projects represent more than historical disagreement. They embody two moral frameworks: one seeks reckoning, the other reassurance.

The experiences of 1619—and the racial hierarchy they produced—were not erased by 1776; they were perpetuated through it. The Revolution preserved slavery even as it proclaimed liberty. The question, then, is why a nation that fought a war for freedom maintained a system of human bondage.

The answer lies in the intertwining of economics, power, and identity. Slavery underwrote the colonial economy, and racial ideology offered both moral justification and social cohesion. The Founders’ universal rhetoric was constrained by material dependence and by fear that genuine equality would unravel their fragile order. The compromise between ideal and interest became the template of American democracy itself.

The continuity from 1619 to 1776—and beyond—echoes in today’s conflicts over education, race, and national memory. Efforts to restrict historical truth reveal how deeply America still resists confronting its origins. The question that haunted the Founders—can a democracy built on exclusion sustain itself?—remains unresolved.

Whether America embraces the truth of 1619 or retreats into the mythology of 1776 will determine how it defines democracy in the twenty-first century. True democracy will emerge only when the nation can face both dates honestly—when it can acknowledge that 1776 articulated freedom, but 1619 exposed its limits. Only through that dual recognition can the country hope to transform its history of contradiction into a future of equality.