Ronald J. Sheehy has a Ph.D. in Molecular Biology. Franca V. Sheehy operated Kumon Math and Reading Centers in Peachtree City, Ga.

Ronald J. Sheehy has a Ph.D. in Molecular Biology. Franca V. Sheehy operated Kumon Math and Reading Centers in Peachtree City, Ga.

For generations, Black educators have observed a troubling pattern: within much of the African American community, math literacy has never carried the same urgency as reading. This disparity is not the result of a lack of ability or ambition. It is the legacy of history. After emancipation, reading was the essential tool of freedom. Newly freed people pursued literacy with extraordinary intensity because it opened the door to contracts, scripture, newspapers, civic life, and political participation. In that moment, reading meant survival. Mathematics, by contrast, did not hold the same immediate relevance and slipped to the margins of educational priorities. That legacy remains with us.

But the demands of the 21st century have shifted dramatically. In an economy increasingly shaped by data, technology, and automation, math literacy is as foundational as reading—perhaps even more predictive of long-term mobility. Decades of research have shown that competence in mathematics, particularly mastery of algebra, is one of the strongest indicators of college completion and entry into STEM fields. Algebra is not a bureaucratic hurdle; it is a gateway into the professions that power the modern economy, including engineering, computer science, finance, and health technology. And recent developments have raised the stakes even further.

Many African American parents do not realize that 50 percent of the SAT score is mathematics. In light of the Supreme Court’s ruling eliminating affirmative action, many colleges and universities have quietly returned to heavier reliance on standardized tests in their admissions decisions. As a result, math performance now carries disproportionate weight in determining access to selective institutions, scholarships, and opportunity itself. For Black students—who often attend under-resourced schools—this reality poses an immediate challenge. Without a strong math foundation, the path to higher education becomes steeper. What was once an educational concern is rapidly becoming a structural barrier.

At the same time, the importance of math literacy is already well understood in many Asian and Indian immigrant households. Families arriving in the United States often place intense emphasis on two pillars: learning English, which eases daily life, and mastering mathematics, which safeguards the future. Children frequently attend weekend math academies, online enrichment programs, and after-school study sessions. Their success is not the product of inherent superiority; it emerges from cultural prioritization. The difference in emphasis yields real consequences, and it reveals what is possible when communities treat mathematics as indispensable.

We also know something earlier generations could not: math success begins in early childhood. By kindergarten, children begin developing “number sense”—a familiarity with numbers, patterns, and spatial reasoning that predicts later achievement in algebra and beyond. This understanding inspired civil rights activist Bob Moses to launch the Algebra Project in Mississippi. Moses saw math literacy as a civil rights issue and believed that algebra could transform the life chances of poor Black students. His work demonstrated that when expectations rise—and when communities support those expectations—children rise as well.

If the Black community intends to prepare its children for a rapidly changing economy, it must treat math literacy with the urgency it once reserved for reading after emancipation. Historical indifference may be understandable in its origins, but it is no longer defensible. Parents, educators, churches, fraternities, sororities, and civic organizations all have a role in elevating math to a central place in the cultural conversation. The pathway begins with early childhood exposure, continues with consistent reinforcement at home and in school, and culminates in a community-wide recognition that algebra mastery is not a barrier but a birthright.

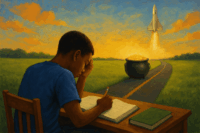

Imagine if Black families embraced math with the same determination once applied to literacy. Imagine if every child entered third grade with strong number sense and a sense of comfort around numbers. Imagine if algebra were expected rather than feared. The outcome would be nothing less than transformative.

The economy of tomorrow is numerical, digital, and quantitative. Without consistent math preparation—beginning early in life and reinforced throughout schooling—Black children will remain excluded from the fields that build wealth and influence. The “pot of gold” is real. But it will belong only to those prepared to claim it. The time to act is now.