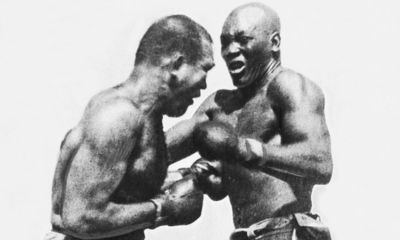

The Fight of the Century Johnson v Jeffries, July 4th 1910

The Fight of the Century Johnson v Jeffries, July 4th 1910

The crisis of masculinity in America is often framed in two familiar ways: either as the destructive force of “toxic” behaviors—aggression, misogyny, domination—or as the struggles of men in a rapidly changing society, uncertain of their place as traditional roles of provider and protector recede. Movements such as MAGA have seized on this tension, promising a return to “traditional” masculinity as a means of securing political loyalty, especially among young white men. What is often missing from these analyses, however, is the role of race. Masculinity in the United States has never been race-neutral. For centuries, white manhood has defined itself in opposition to Black masculinity, casting the latter as a threat to be contained, humiliated, or displaced.

The psychological battles of masculinity are not abstract. They unfold on concrete stages, beginning with high school gyms and football fields, extending through college stadiums, and culminating in professional arenas broadcast daily into homes across the country. These settings do more than entertain; they socialize boys into particular notions of manhood. Winning, toughness, and domination are celebrated as the hallmarks of masculine identity. Yet for white young men, these stages often deliver a contradictory message: the athletes most admired, most dominant, and most culturally influential are overwhelmingly Black.

This dynamic produces a paradox. On one hand, Black athletic achievement has inspired admiration and even idolatry among many white fans. On the other, it triggers resentment, a gnawing sense that white masculinity is being displaced in the very arenas where it once reigned supreme. High school athletes encounter it directly, competing with or against Black peers. College students witness it in the spectacle of majority-Black basketball and football teams drawing crowds and revenue. And on television screens, the image of Black male dominance in professional leagues is inescapable.

This tension has deep historical roots. The early 20th century panic over Jack Johnson’s victories in the boxing ring produced cries for a “Great White Hope,” as if white manhood itself were at stake in the outcome of prize fights. During Jim Crow, the myth of Black male sexual threat was weaponized to justify lynching and segregation. And in the mid-20th century, the integration of major league sports became a flashpoint for racial backlash, precisely because athletic success carried symbolic weight far beyond the field.

Today, right-wing media and podcasts magnify these dynamics into explicit political rhetoric. The sight of Black athletes excelling—and worse, speaking politically—becomes evidence that white masculinity is under attack. Colin Kaepernick’s kneeling against police brutality, for example, was quickly reframed by conservative voices not as a principled protest but as an affront to national loyalty and manhood. The point was clear: Black athletic power, when coupled with political expression, represented not just competition but humiliation for white men.

Beneath all of this lies one of the oldest contests between men: the competition for women. White male fears of Black masculinity have long been tied to sexual rivalry. The myth of Black male desire for white women fueled some of the most violent episodes of racial terror in American history. In the modern era, the visibility of successful Black athletes with interracial relationships has reignited these insecurities. In this sense, the stadium is not just a stage for athletic competition; it is a symbolic battlefield for sexual and social dominance.

The result is a politics of radicalized hyper-masculinity. By casting Black men as rivals and threats, MAGA rhetoric taps into the centuries-old structure of white manhood defined through opposition. It reassures white males that they can reclaim their “rightful” place atop hierarchies that now appear unsettled. The stadium thus becomes a metaphor for society itself: a place where white men are urged to fight to restore their dominance, even as the visible reality shows them losing ground.

To understand the present crisis of masculinity, we must see it not only as a clash of gender roles but as a racialized drama, staged in gyms, stadiums, and media platforms across the country. The competition between white and Black men—over recognition, resources, and women—remains central to American life. And as long as politics continues to inflame rather than resolve these insecurities, the arenas of sport will remain the proving grounds where masculinity is both performed and contested.