Featured

We Must Fight for a Better America. We Have No Choice. By Siva Vaidhyanathan / The New Republic

We Must Fight for a Better America. We Have No Choice. By Siva Vaidhyanathan / The New Republic

The problem isn’t “polarization.” The problem is white supremacy.

We can’t predict if the United States will survive as a democratic republic until 2050. It’s barely one in 2022. But we can imagine what it would take to make it one. In fact, for the survival of millions of Americans and billions around the world, we must ensure it does.

To do so, we should boldly articulate a vision for the United States that we have only occasionally aspired to convey: that of a fully democratic, cosmopolitan republic that finally rejects white supremacy as an organizing American ideology. It should be one that values and strengthens deliberation as the chief instrument of decision-making. And it should emphasize that we have a shared fate—not only as Americans but as humans on a threatened planet. Anything less risks disaster, both slow and fast. Read more

Related: A new day? Voters stood up for democracy — and now we have the data. By Chauncey Devega / Salon

Georgia Runoff

What Warnock’s Win in Georgia Means for 2024. By Ronald Brownstein / The Atlantic

What Warnock’s Win in Georgia Means for 2024. By Ronald Brownstein / The Atlantic

Democrats hold a key advantage in the five states that will decide the next presidential election.

Senator raphael warnock’s win in yesterday’s Georgia Senate runoff capped a commanding show of strength by Democrats in the states that decided the 2020 race for the White House—and will likely pick the winner again in 2024. With Warnock’s victory over Republican Herschel Walker, Democrats have defeated every GOP Senate and gubernatorial candidate endorsed by Donald Trump this year in the five states that flipped from supporting him in 2016 to backing Joe Biden in 2020: Michigan, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Georgia, and Arizona. Read more

Related: Senate Democrats just picked up one more vote. Here’s what that means. By Juma Sei / NPR

Related: Raphael Warnock Beat Herschel Walker; Georgia Is Still Red.By New York Magazine

Political / Social

Republicans Want the Supreme Court to “Rewrite History” So They Can Hijack Elections. By Ari Berman / Mother Jones

Republicans Want the Supreme Court to “Rewrite History” So They Can Hijack Elections. By Ari Berman / Mother Jones

During the Moore v. Harper arguments, a majority of justices expressed skepticism about the radical “independent state legislature” theory.

A lawyer for the GOP-controlled North Carolina legislature argued before the Supreme Court on Wednesday that state legislatures should be granted sweeping new powers to pass gerrymandered maps and restrictive voting laws and cannot be constrained by state courts or state constitutions when it comes to regulating federal elections. This “independent state legislature” theory had long been considered fringe, but in recent years it has been aggressively pushed before the court by Federalist Society co-chairman Leonard Leo and his allied groups, the Trump campaign during its attempt to overturn the election in 2020, and now by Republican state lawmakers in North Carolina. Read more

Related: Supreme Court hears case that could reshape US election laws. By Alexandra Hutzler / ABC News

Related: Why the Other Eight Justices Must Censure Clarence Thomas. By Amanda Frost / Slate

Senate passes bill to protect same-sex and interracial marriage over GOP opposition. By Sahil Kapur / NBC News

Senate passes bill to protect same-sex and interracial marriage over GOP opposition. By Sahil Kapur / NBC News

The bill now goes back to the House for a final vote before it heads to Biden’s desk.

The Senate passed landmark legislation Tuesday that would codify federal protection for marriages of same-sex and interracial couples, with Democrats securing enough votes to overcome opposition from most Republicans. The Respect for Marriage Act was approved 61-36, with support from all Democrats and 12 GOP votes, after a filibuster was defeated and three amendments offered by Republicans who oppose the bill were rejected. Read more

The Culture War on Public Education. By Peter Greene / The Progressive

The Culture War on Public Education. By Peter Greene / The Progressive

It’s time to recognize the real target of the book bans and gag orders dominating national headlines: your local school.

It seems like ages since so many of us suddenly had to take a crash course in critical race theory (CRT). Then, seemingly five minutes later, just as Christopher Rufo, a fellow at the conservative Manhattan Institute, had promised, the CRT panic broadened into the “culture wars,” fought on a dozen different fronts by educators: “Don’t say gay” laws, “anti-woke” legislation, calls to ban books, gag laws for teachers, and private rights of action, so that parents could sue schools any time they felt a line had been crossed. Culture wars continue to flare, but we should be discussing their true victims. Read more

New Report: Faculty Remain Stubbornly White. By Jon Edelman / Diverse Issues In Higher Ed.

New Report: Faculty Remain Stubbornly White. By Jon Edelman / Diverse Issues In Higher Ed.

Despite pledges from campus leaders to diversify all facets of their institutions, faculty have remained stubbornly white, according to a new report from the Education Trust, a non-profit that works to close opportunity and achievement gaps.

“It reflects something that we’ve long known,” said Dr. Kimberly A. Griffin, professor and dean of the College of Education at the University of Maryland. “That the student body is diversifying much faster than the faculty is.” 57% of schools had failing grades for Black faculty diversity, and 79% had failing grades for Latinx diversity. Only 13% of colleges received the highest possible grade when it came to African Americans, and only 7% received top marks for Latinx diversity. Read more

Related: Med schools should de-emphasize standardized admissions tests. By Alessandro Hammond and Cameron Sabet / Wash Post

A new website unravels media coverage and ‘missing white woman syndrome.’ By Jonathan Franklin / NPR

A new website unravels media coverage and ‘missing white woman syndrome.’ By Jonathan Franklin / NPR

Thousands of people are reported missing in the United States each year. And while not every missing person case will get widespread media coverage, the fight to locate them — whether alive or dead — is always the main priority.

However, when it comes to missing person cases involving people of color, that same media attention quickly dissolves, ultimately feeding into the phenomenon of ‘Missing White Woman Syndrome‘ — a phrase coined by the late journalist Gwen Ifill that addresses the media’s fascination with covering attractive, middle class-looking white women in comparison to missing persons of color. Read more

Ethics / Morality / Religion

A Pastor and Politician Who Sees Voting as a Form of Prayer. By Katie Glueck / NYT

A Pastor and Politician Who Sees Voting as a Form of Prayer. By Katie Glueck / NYT

Credit…Nicole Craine for The New York Times

He likened voting to a “prayer for the world we desire,” and called democracy the “political enactment of a spiritual idea,” that everyone has a divine spark. He invoked the legacies of civil rights heroes and “martyrs” who fought and sometimes died for the right to vote, even as he promised to pursue bipartisanship in pressing his policy ambitions. He is a man of deep faith, the senior pastor at the Atlanta church where the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. once preached. And he is also a political tactician who has long believed that “the church’s work doesn’t end at the church door. That’s where it starts.” Read more

Antisemitism isn’t just ‘Jew-hatred’ — it’s anti-Jewish racism. By Dan Waxman / Religion News

Antisemitism isn’t just ‘Jew-hatred’ — it’s anti-Jewish racism. By Dan Waxman / Religion News

Combatting antisemitism isn’t just about ‘calling it out’ — it’s about helping people understand what antisemitism is in the first place.

Probably the most common form of antisemitism consists of negative stereotypes about Jews, such as the idea that they are rich, greedy, scheming or more loyal to other Jews or to Israel than to the countries in which they live. These stereotypes are embedded in many cultures, and they can be unconsciously internalized. People can therefore express antisemitic stereotypes without knowing their racist origins, or harboring hostility toward Jews. Read more

Related: Doug Emhoff hosts a roundtable on antisemitism at the White House. By Franco Ordonez / NPR

The Empty Gestures of Disillusioned Evangelicals. By Michelle Goldberg / NYT

The Empty Gestures of Disillusioned Evangelicals. By Michelle Goldberg / NYT

The televangelist Robert Jeffress at the White House in 2020.Credit…Evan Vucci/Associated Press

There have been encouraging signs lately of influential evangelicals inching away from Donald Trump. The Washington Post last month quoted a self-pitying essay by Mike Evans, a former member of Trump’s evangelical advisory board, who wrote: “He used us to win the White House. We had to close our mouths and eyes when he said things that horrified us.” Religion News Service reported that David Lane, the leader of a group devoted to getting conservative Christian pastors into office, recently sent out an email criticizing Trump for subordinating his MAGA vision “to personal grievances and self-importance.” Read more

Historical / Social

Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s pending promotion sheds new light on his overlooked fight for equal rights after the Civil War. By Anne Marshall / The Conversation

Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s pending promotion sheds new light on his overlooked fight for equal rights after the Civil War. By Anne Marshall / The Conversation

Like most white Northerners, Grant signed up to fight for the Union – not for emancipation. But by 1862, the freedom of enslaved African Americans had become vital to the Union war strategy, if not yet its cause.

A year before President Abraham Lincoln signed in 1863 the Emancipation Proclamation that freed enslaved people in the Confederate states, Grant oversaw the establishment of refugee, or contraband camps, throughout the Mississippi Valley. Those camps provided basic housing, food and work for Black men and women who had fled from slavery. Grant also administered the enlistment of African American men into United States Colored Troops units during the Vicksburg campaign. Read more

Should schools late to desegregate offer reparations? By Petula Dyorak / Wash Post

Should schools late to desegregate offer reparations? By Petula Dyorak / Wash Post

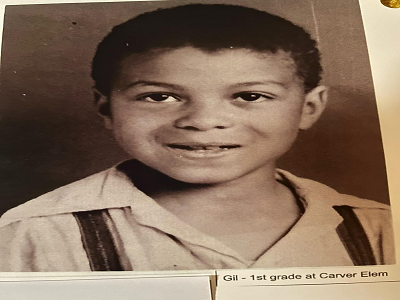

Gilbert Timbers was among the first cohort of Black schoolchildren in Virginia allowed to leave his segregated school in Loudoun County in 1965. (Gilbert Timbers)

That acrid smell of fresh ink still brings Gilbert Timbers back to his first federally mandated days in a new high school. As a Black child, he’d been shut out of it until 10th grade, 11 years after a U.S. Supreme Court decision compelled the nation’s public schools to desegregate. “Everything at Douglass was hand-me-downs. The schoolbooks had broken spines and fell apart in our hands,” said Timbers, 74. “But I remember the smell of those new books at Loudoun Valley. Everything in that school was fresh and clean.” But the case of segregation in this county offers a discrete set of people and circumstances. Many of the kids kept out of the White schools are still around. They’re adults who can trace the contours of a journey rooted in less opportunity and more challenges than their White peers. Read more

How African Americans Entered Mainstream Radio. By Bala James Baptiste / AAIHS

How African Americans Entered Mainstream Radio. By Bala James Baptiste / AAIHS

“Roi Ottley on radio quiz program,” circa 1945 -1959 (Schomburg Center/ NYPL)

For nearly 50 years, commercial radio companies only employed white broadcasters to target information and entertainment to mainstream America. The exclusion of African Americans in broadcasting began with the emergence of the first commercial radio station in the United States, KDKA, in Pittsburgh on November 2, 1920. As radio advanced, some Northern radio stations featured Black broadcasters. However, the primary depiction of African Americans on-air came from white radio personalities who portrayed them as comical, non-intellectual, and without virtue. Read more

Billie Holiday and the Black Arts Movement. By Whit Frazier Peterson /AAIHS

Billie Holiday and the Black Arts Movement. By Whit Frazier Peterson /AAIHS

Billie Holiday, Washington, D.C., 1948 (Wikimedia Commons)

The Black Arts Movement (BAM) was a controversial, politically charged cultural uprising, which James Smethurst, in his eponymous study of the era, calls “the cultural wing of the Black Power movement.” Billie Holiday’s appeal to the BAM is undeniable, and her influence on it is still understudied. In one of the most expansive anthologies of the movement, Black Fire, the poems “The Singer” and “Elegy for a Lady”( written by James Danner and Walt Degall respectively) pay tribute to Billie Holiday. Sonia Sanchez celebrates Holiday in her piece “liberation / poem.” Read more

‘Loudmouth’: Rev. Al Sharpton reflects on a career as a ‘blowup man.’ By Michael O’Sullivan / Wash Post

‘Loudmouth’: Rev. Al Sharpton reflects on a career as a ‘blowup man.’ By Michael O’Sullivan / Wash Post

The Baptist minister, civil rights activist and talk show host has made it his life’s work to call attention to racism and racially motivated violence

The documentary “Loudmouth” opens with a stark contrast: a shot of the Rev. Al Sharpton as he walks toward the chair in which he’ll sit for the course of the roughly two-hour movie as he reflects on his career as a civil rights activist. Dressed in a dapper gray three-piece suit, with his salt-and-pepper hair slicked neatly back, Sharpton, who turned 68 in October, cuts a very different figure from the early 1980s footage of him that director Josh Alexander intersperses amid the interview segments that form the spine of the film — and not just because the Brooklyn-born Baptist minister and MSNBC host has famously lost so much weight. (Sharpton reportedly went from over 300 pounds to around 130.) At area theaters. Contains some mature thematic material. 123 minutes. Read more

Sports

Deion Sanders’ exit from Jackson State shows why HBCUs keep struggling. By Jesse Washington / Andscape

Deion Sanders’ exit from Jackson State shows why HBCUs keep struggling. By Jesse Washington / Andscape

Coach Prime is leaving the best Black college team for a doormat program at a predominantly white college

He’s leaving for Colorado, an underperforming team in the downward-spiraling Pac-12 conference. The Buffaloes have only had two winning seasons since 2005. Six of the last seven coaches got fired. I grew up watching Sanders be Prime Time; Colorado football plays on Nowhere Standard Time. Adding insult to injury, only 2.6% of its more than 36,000 students are Black. Read more

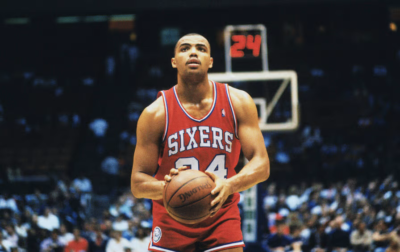

The Political Story of Charles Barkley. By Dave Zirin / The Nation

The Political Story of Charles Barkley. By Dave Zirin / The Nation

On this week’s episode of the Edge of Sports podcast, Tim Bella joins the show to talk about his new biography of Charles Barkley.

We talk to Bell about how Barkley’s upbringing and experiences shaped Chuck into the person that we see every week on our TV sets. We also have Choice Words about I also have some choice words about the politics surrounding the push for Brittney Griner’s freedom. Listen here

Celtics interim coach Joe Mazzulla always had faith he’d be an NBA coach. By Marc J. Spears / Andscape

Celtics interim coach Joe Mazzulla always had faith he’d be an NBA coach. By Marc J. Spears / Andscape

After taking over for Ime Udoka, the 34-year-old has Boston thriving. He talks to Andscape about his Black and Italian roots, the pressure of coaching the legendary franchise and more.

Mazzulla gave Andscape an exclusive interview from his hotel suite the night before the Celtics’ 117-109 road win against the New Orleans Pelicans on Nov. 18. The former West Virginia University star guard talked to Andscape about his mentality after accepting the Celtics head coach job under turmoil, Udoka, the interim tag, the pressure of coaching a franchise with 17 NBA championships, keys to returning to the NBA Finals, coaching Tatum and Brown, studies in sports psychology, words of wisdom from West Virginia men’s basketball head coach Bob Huggins, the state of Black NBA head coaches through the eyes of being Black and Italian and much more in the following Q&A. Read more

Nike parts ways with Kyrie Irving after antisemitism controversy. By Ben Golliver / Wash Post

Nike parts ways with Kyrie Irving after antisemitism controversy. By Ben Golliver / Wash Post

Irving, 30, had been one of the brand’s most visible endorsers since his first sneaker was released in 2014. The Athletic first reported the end of the eight-year partnership, and Irving’s agent, Shetellia Riley Irving, told CNBC that the sides had “mutually decided to part ways.” Nike co-founder Phil Knight told CNBC at the time that Irving had “made some statements we just can’t abide by” and said he “doubted we would go back” on the suspension. Read more

Site Information

Articles appearing in the Digest are archived on our home page. And at the top of this page register your email to receive notification of new editions of Race Inquiry Digest.

Click here for earlier Digests. The site is searchable by name or topic. See “search” at the top of this page.

About Race Inquiry and Race Inquiry Digest. The Digest is published on Mondays and Thursdays.

Use the customized buttons below to share the Digest in an email, or post to your Facebook, Linkedin or Twitter accounts.